Introduction to Cursive Handwriting A Multisensory perspective

A presentation of our thoughts, ideas, information and social communication is normally in a spoken language as spoken sounds (strong dialects can change our auditory language so profoundly that it may seem like learning a different language). Never the less this spoken language can also be successfully communicated through the written form using the visual presentation of alphabet letters specifically organised to represent the spoken word.

Written communication starts with movement and integrates our main sources of sensory information as illustrated in the diagram below:

Cursive handwriting adds a flow of movement that can integrate the written language into a holistic expression of calligraphy, personal expression and interactive communication.

The important difference between hand written communication and printed material is respectively that of a personally identified audience and specific reader/s, versus a common unspecified audience. The author has written poetry but the contents were not written for any future even. Each poem was inspired by a particular desire to communicate something special to someone special and ‘the someone special’ included the author herself. The poems thus formulated a communication beyond that which could have been spontaneously spoken, inspired by thoughts beyond those of normal everyday conversation.

Maria Montessori presented that learning to write is a natural passion for children which evolves as a visual form of language communication, i.e. one that is seen as visual symbols rather than heard as auditory sounds. For the young child who has learnt his mother tongue intuitively from birth this visual presentation of that rich and diverse means of communication comes as an exciting and inspiring alternative, once the child has gained an understanding of this potential, the written media offers the additional extensive resource of recorded spoken language.

Cursive Handwriting

Mastering how to join written letters involves a complex integration of the following skills:-

Where to start.

How to move in a left to right direction across the paper.

How to produce the correct sequence of drawn shapes with a continuous line.

How to exit the letter shape at the correct place and travels along to produce a joining line that enters the next letter at the correct lower or midway starting point

the letter q is an exception in that, even within cursive script, it is allowed to remain separate from the following letter.

Individual letter shapes required for the production of cursive handwriting are presented below in a repeated format that illustrates how the letters join one to another. The specified cursive handwriting movements for the production of a single simple letter shape are combined to form the more complex letter shapes. Learning to write the more complex letter shapes involves a combination of different co-ordinated handwriting skills.

Maria Montessori recorded that the children she was teaching, within the freedoms of child-directed learning, choose to learn to write before and thereby as a prerequisite to their learning to read. Learning to read was a natural by-product of learning to write as a form of personally meaningful communication. This perspective also meets the theory, and supporting observations, that young children are motivated to learn from their own egocentric perspective of what and how they want things to be. From the child’s own inner perspective and motivation the written language is a permanently preserved form of communication that cannot be easily or covertly disrupted. Montessori saw this as the children developed the desire to write notes instead of normal speaking and listening styles of open communication. There certainly seems to be an aspect of written communication that gains some sort of command over the reader’s attention.

In our present lifestyle spoken communication is rarely heard without the competition of other background noises as well as the spoken sounds of other people talking, and the possibility of spoken interruptions that may disrupt the speaker’s desired delivery of communication and subsequent influence. For these reasons the visual medium of printed and written words is in itself capable of commanding a focus of its own. This visual modality holds a level of separateness from the surrounding auditory geography. A normal auditory environmental experience may include multi-layered forms of spoken communication simultaneously present within a single persons hearing at any one time. Some children and adults have hearing difficulties related to auditory integration rather than any physical hearing deficit within the mechanics of the hearing organ itself. This type of hearing deficit occurs when the background sound geography disrupts the person’s auditory perceptual skills and related auditory integration processes within the brain. Thus, the visual modality of written communication can in itself give us a more personal and focused form of communication. Some young readers who have established an early ability to read stories, cereal packets and information boards, illustrate a very clear ability to shut out auditory stimulus and focus on the communication presented by the printed words even when the content is beyond their level of understanding. In some cases early reading skills can establish a self-imposed means of separation or even isolation from creative activities and social opportunities for interaction, sharing and intimacy.

The author has observed how some young early readers can appear to select indiscriminately any available reading activity as a priority above that of other forms of social interaction or creative free-play activities.

Steiner presented very clearly that reading and writing are skills should not be taught or encouraged before the age of seven. This he presents is to protect the child’s natural creative and social development in the preceding years. There does not appear to be any clear evidence that illustrates early intellectual learning before the age of seven has a detrimental effect upon other critically sensitive areas of development. However, this philosophy within the Steiner education does not appear to compromise the children’s intellectual and academic development and many parents and teachers firmly believe they see advantages. Other aspects could be advantageous to those children who have received Steiner Education or indeed any other form of alternative education that does not focus on the more intellectual aspects of academic learning during the infant and junior range of schooling. For example it is also commonly found that Alternative Schools have smaller classes. This difference in the number of children can influence not only the amount of one to one teacher – pupil interaction but also the amount of peripheral auditory and visual environmental stimulus that could potentially disturb a child’s personal ability to focus. The author would question whether the present high level of text communication now present within senior school pupils is indeed a desperate attempt at making up for a shortfall in focused personal communication. The present intensity of media and other persistent environmental stimulus often excludes everyone from attaining focused attention through personal and/or private spoken communication. In most social contexts offered within secondary school education, conversations and related social interaction could be subject to easily, accidentally and indeed unavoidably being: over-heard, interrupted, embraced by those not directly involved, judged and questioned by others who consider themselves older and wiser, or likely to be influenced by related consequences. These examples illustrate important differences between the quality of space for individual focus versus over stimulating and socially intense environments due to the industrial revolution, rising population and high inner city populations and over-crowding. The effect this has on children’s school education and later working and family life can be easily observed as noise pollution and highly intense social influences.

Thus learning to write gives children an alternative medium for recording and expressing their own thoughts and inner knowledge, learning to read gives children another way of receiving the thoughts and knowledge of others without the need for the personal connection required for spoken communication. This impersonal aspect present in the medium of printed material is considered to make learning to read an activity not suited to young children who can easily gain an ability or indeed an obsession for reading material both fiction and non-fiction that is beyond their age and their practical understanding. Steiner presented that early reading separated the child from their own imaginative thinking and from natural social interaction and social development, their own joyful creative activities and holistic intellectual development.

The Author considers the true definition of handwriting to be that of joined script, in that a person can choose to personalise their handwriting into one of separated letters but without the ability to produce joined handwriting one’s personal choices are restricted. Words written as individual letters do not present the natural flow of sounds within each spoken word: cat – cat. Also if we are in a flow of creative thought it may be very helpful to write notes in a quick easy flowing script/scribble. This gives a vague chance of keeping up with the speed of focused and creative thinking. For these reasons this chapter is going to focus on the learning of joined handwriting to serve as a speedy and legible form of visible language. Therefore this handwriting is proposed as a practical tool rather than the art of calligraphy. The didactic materials present a simple structure for successful production of cursive script. Flow and legibility are more important than personal style and aesthetic standards of production.

Using chalk to write on a large blackboard may produce excellent joined handwriting and requires the same skills as those needed for smaller writing with pencil and paper. Once the basic foundation skills have been established they can be practised and thereby established in a smaller or lager format, according to the individuals own will.

Basic Foundations

Elements within the ability to produce hand written communication would normally include the following:-

a. The desire to make meaningful marks as symbols of communication.

b. The ability to coordinate start and stop with the writing implement.

c. The ability to draw a continuous line.

d. The ability to draw a straight line in both the horizontal and vertical directions.

e. The ability to draw a curved line that starts and stops at the same point.

f. The ability to identify three horizontal zones, upper zone, main zone, and lower zone.

g. The ability to trace over a previously drawn line.

h. The ability to start and stop within the specified range of zones.

•

A Continuous Line Game

Exploring the A continuous line could be considered as the first principle of handwriting.

The following picture (A) shows two children, of very different ages and ability each creating a continuous line,

Picture (B) shows them playing the Follow My Line game indoors.

• This game of follow my line is played in the last picture (C) with the added element that one person is also giving Stop and Go instructions. Now the continuous line gains a time structure that embraces pauses, moments of stillness and anticipation. This game can be played in the sand on a beach where with the aid of long sticks the participants can move over a large open area. Also participants can make and follow a continuous line on any suitable large outdoor surface using chalk, (large pieces of natural chalk are ideal for this game.)

Pre handwriting skills are notably associated with basic craft activities and the 2D foundations in art and design, and form-drawing.

Plaiting, Finger Knitting, French Knitting, traditional knitting and crochet activities present a 3D kinaesthetic presentation of a continuous line combined with the numerical concept of adding a repeated rhythmical movement to make it bigger and bigger and bigger.

Within many aspects of art and craft activity there are underlying elements of rhythm that illustrate patterns of repetition. This is the element that is focused upon during the extra years in Steiner Nurseries when the older children are encouraged to develop their sewing, weaving and knitting skills. Many young children in Steiner school education produce very successful handicraft work prior to their initial introduction to formal learning. Steiner advocated teaching children to write words in capital letters before teaching cursive writing, alongside an associated level of form drawing.

The author had designed the following gated cursive handwriting font that helps children to learn through a self-directed discovery approach. This gated design indicates where a letter may begin and where to exit one letter shape and join it to the following letter.

[This font and other variations are presented in the ‘Print It Yourself’ files for the ‘Read, Write and Spell’ teaching materials designed by Helena Eastwood]

Structural Perspectives on Cursive Letter shapes

Traditional handwriting patterns and form-drawing

Traditional handwriting patterns and form-drawing present the following skills within one continuous drawing movement:-

Curly candy canes……..

• Reflection through the vertical line of symmetry

• Reflection through the horizontal line of symmetry.

• All four compass directions and related symmetry.

A Structural Presentation of Basic Letter Shapes.

The basis shapes shown below were originally designed by the author when she created her own font.

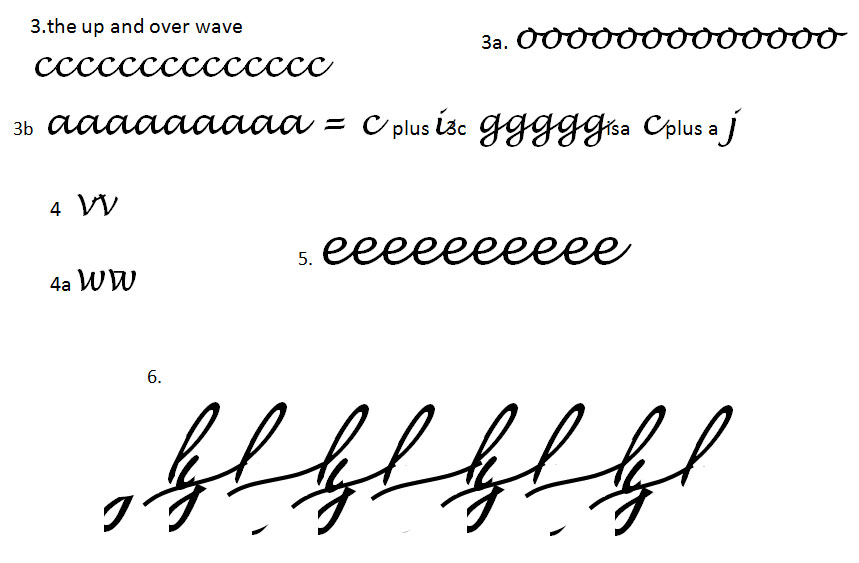

This set of letter shapes illustrate how some letters have one letter shape and others are a combination of more than one written shape produced consecutively.

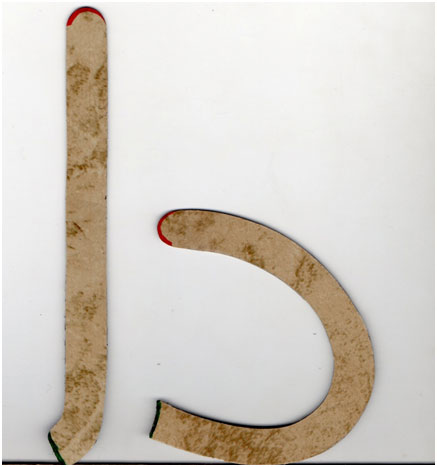

Where to enter and exit the letter is marked in green and the red line represents a stop barrier. The black line shows where each individual shape sits on the base line. These shapes were cut out of plastic adhesive tiles stuck back to back then cut out (the edges were sanded to give a smooth finish) make a set of flexible flat durable shapes. These 3 dimensional shapes provide a medium that bridges the difference between 3D objects and 2D symbolic representation. The shapes are stacked in the order that they are written to produce cursive handwriting as shown in the illustration below:-

The two options for writing a cursive ‘b’ are presented as individual pieces. When teaching the author tries to establish if a particular style appears to be favoured. Then only the shapes that match are presented to support further exploration and understanding. If there are no signs that the second form of script is preferred the author presents and teaches the first example.

Mastering how to join Cursive Handwriting

Mastering how to join written letters involves a complexity of:-

Where to start.

How to move in a left to right direction across the paper.

How to produce the correct sequence of drawn shapes with a continuous line.

How to exit the letter shape at the correct place and travels along to produce a joining line that enters the next letter at the correct lower or midway starting point

the letter q is an exception in that, even within cursive script, it is allowed to remain separate from the following letter.

Individual letter shapes required for the production of cursive handwriting are presented below in a repeated format that illustrates how the letters join one to another. The specified cursive handwriting movements for the production of a single simple letter shape are combined to form the more complex letter shapes. Learning to write the more complex letter shapes involves a combination of different co-ordinated handwriting skills

Thus the letter ‘a’ is written as a combination of (3) c plus (1)i

There are two different ways of producing a cursive letter ‘b’. This style of cursive bbb starts with a tall up-stroke (2) and then creatively uses the latter part of o movement. The alternative way to produce a cursive ‘bb’ is another creative combination of the tall up-stroke as a loop, or better still, a simpler single up and ‘retrace’ downward movement (2), followed by an inverted o. Being the second letter of the alphabet the letter ‘b’ can present early learners with a complex and possibly confusing skill of correct movement for the handwritten visual presentation.

The curly c is a standard movement presented as number two in the above diagram.

The letter d could also be considered challenging in the initial learning stage, especially for young children with little experience and limited foundations skills. It starts with the curly c and completes with a tall up and down stroke ddd.

The cut out lino shapes illustrated above can support the learners understanding of how some letters are produced as a combination of different handwriting movements. The author has found this three dimensional kit can resolve issues of confusion related to letter orientation such as ‘p’, ‘b’, ‘d’, and ‘q’. Children whose handwriting has been prone to the reversal of letter shapes have been seen to resolve this type of confusion after working with the 3D letter building shapes. (The full set of shapes a to z ispresented in the Print It Yourself file called ‘Cursive Letter Building Kit’.