Contents:

The life’s work of Steiner and Montessori

- Child development during the early years

The Sensitive Periods

ORDER(1st– 4th year);-

SENSES (1st – 9th year)

SMALL OBJECTS (2nd – 5th year)

WALKING(2nd -5th)

LANGUAGE(Birth to 5th year)

SOCIAL ASPECTS(4th – 7th year)

- Abstract Learning. Concrete.

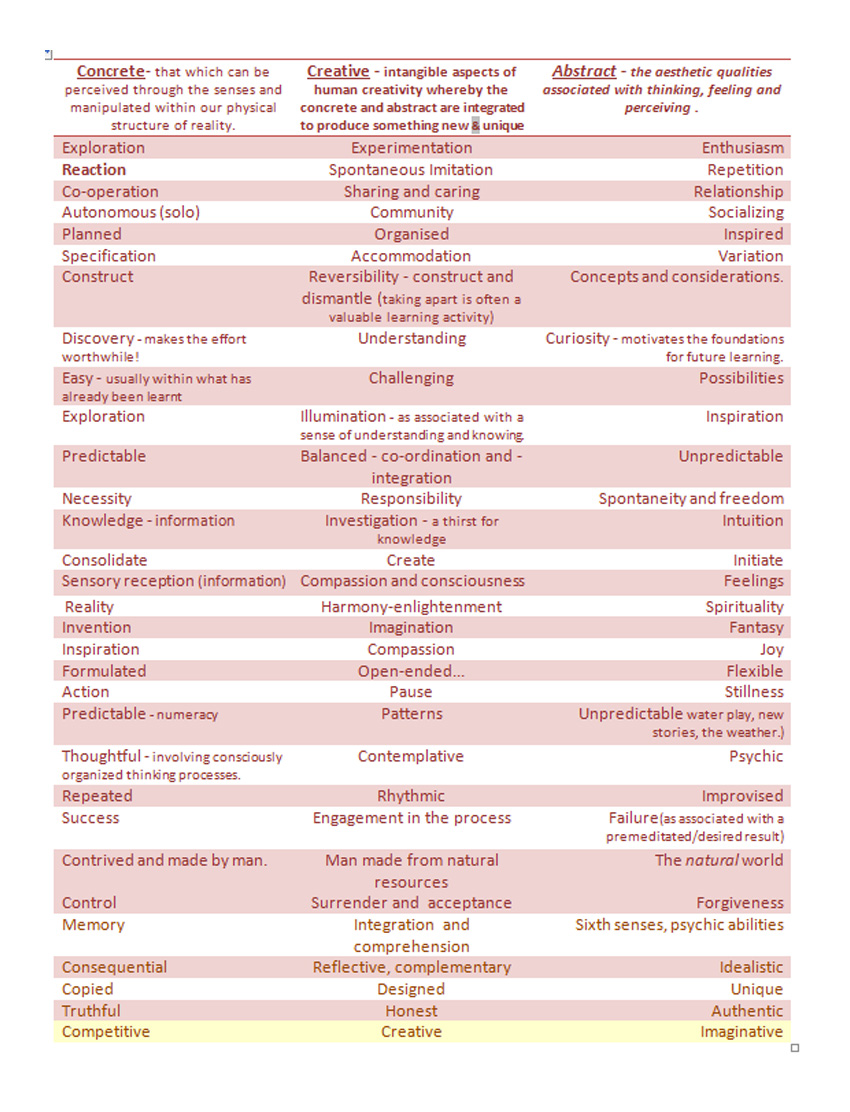

Comparing Steiner and Montessori Philosophy the chart

Development of Assimilation and Accommodation

The Zone of Proximal Development ( ZPD)

Occupational Versus Educational Activity

Child-directed Learning and Creativity

- Abstract & Concrete Thinking

- Child development from random movement to the integration of creative expression with creative production,

Creativity as a union of environmental activity with feelings,

- Supporting Children’s Creativity and Creative thinking

- Integration of Concrete and Abstract Perspectives

Supporting enhanced creativity and self-directed learning.

- Simplify

Bibliography

The life’s work of Steiner and Montessori is emanated all over the world. Although they both worked as individual pioneers much of what they presented appears to be in harmonious agreement. The author has also perceived many aspects of their respective pedagogy infused within the more recent collaboratively developed philosophies and practices in early year’s education, such as High Scope and Reggio Emilia.

Their respective life histories summarised below give some indication of how their own early childhood and subsequent education may have inspired their later pioneering work as adults; firstly in nursery education and later extending into all areas of education.

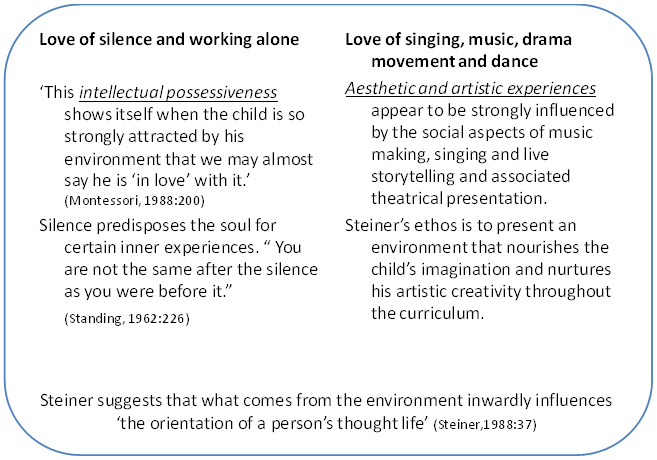

Their two respective philosophies described briefly in the following chart embrace their own approaches to facilitating a natural appreciation of the young child’s natural play and learn disposition.

Steiner philosophy

|

Montessori Philosophy

|

When the teaching adult can relate to the individual soul nature of each child, she will gain powerful feelings of support ‘for teaching and educating the child lovingly’ and the children will respond with ‘loyal affection and devotion’(Steiner,1982:58 &60).Montessori describes the adult is the directress. However, this does not imply that she wishes the children to copy her actions or that she is there to correct a child if he does something wrong. Maria Montessori completely trusted the children’s ability to learn when given appropriate learning materials and an adult presentation of how the materials can scaffold the child’s natural desire to learn and strive for specific results. .

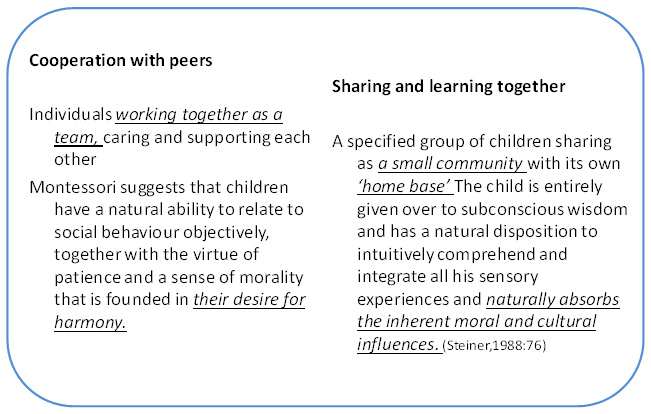

Steiner believed that young children are entirely given over to subconscious wisdom and thereby have a natural disposition to intuitively comprehend and integrate all their sensory experiences. He presented that children naturally absorb the inherent moral and cultural influences presented within their daily life. Steiner perceived that it was the enactment of the child’s will,rather than intellect, that formulates the child’s early learning. Therefore, there is minimal need for correction at this age because the children’s own desires and sense of aesthetic appreciation will facilitate assessment of results and of rhythms of routine, order and tidiness. Admiration and respect for the guardianship role of the adultinitiates loyalty and a desire to please. (Steiner,1988:76)

Rachel Piney (11.7.1909-19.10.1995) Pioneered the concept of ‘Learner Directed Learning’ and she presented that every child is his/her own best expert and when given a sympathetic and supportive adult s/he would be able to organise their own optimum learning strategies.

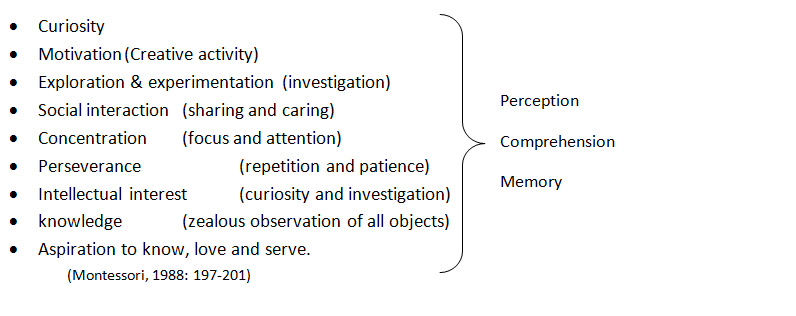

Child development during the early years

Steiner and Montessori both emphasised that free play is very important for all aspects of children’s development. The chart below presents the different aspects of play and learning and the intrinsic relationship between freedom to play and child directed learning

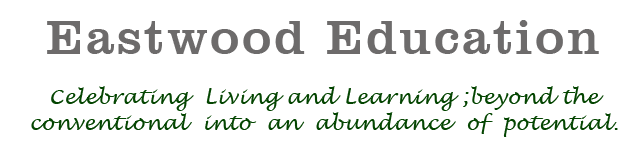

Montessori considered that the children found independence through organised learning. She wrote: ‘Without concentration it is the objects about him which possess the child…..But once his attention has focused, he becomes his own master and can exert control over his world.’ She perceived that following the development of concentration comes perseveranceand repetition which consolidate the child’s ‘ability to carry through what he has begun.’ (Montessori,1988:197-198.)

Both Montessori and Steiner encourage that boundaries should be presented in a way that is perceived as helpful to all rather than disciplinary action focused on a specific individual and/or their chosen activity.

Montessori suggests that it is important the adults do not generally (apart from exceptionally disruptive behaviour) interfere at this early stage of social development when the child’s freedom can be directed by the adult’s careful preparation and organisation of the environment. She also presents that it is important not to have too many things in the classroom and only one specimen of each object because this guides each child to respect the work of others, to wait his turn, integrates the social life of the class and develops important social qualities. Both Steiner and Montessori considered mixed gender and a mixed age range is beneficial to young children because the older children feel a desire to help and protect the younger ones and the younger ones admire the older children, thus the class becomes a group ’cemented by affection’ and the ’atmosphere of protection and admiration’ inspires the children ‘to come to know one another’s characters and to have reciprocal feeling for each other’s worth.’ (Montessori, 1988:206)

Steiner emphasizes the balance in teaching, which is listening and watching (that which comes inward from the outside) and the autonomous activities of doing(that which is anoutward expression from within).(Steiner,1982:35) The Steiner curriculum is predominantly one of music, narrated stories and poetry, theatrical arts, movement, painting and colourful art and crafts, all of which is directly related to the natural world and expressed through the child’s own creativity and imagination. Unresolved issues around the style of presentation and suitability of content presented in picture and story books, TV programmes, and computers games for young children (0-7years) could be described as follows:-

Can the young child distinguish between fantasy and reality within the presentation of an imaginative fairy story? Is the young child’s thinking capacity predominantly influenced by visualisation or language? How does the quality of presentation, i.e. personal presentation/ performances, read from a book, or watched on a screen, influence the child’s ability to appropriately interpret dramatic presentations of imaginative Story and Drama in relation to their own reality? How is the young child’s interpretation of what is real influenced by their own sensory experiences and their ability to identify the abstract qualities of fantasy through either a linguistic or visual media? How does the influence of fantasy relate to the young child’s knowledge of reality and internal social development? What subtle influences of mood, body language, presentation, and social context etc. affect the context within which a child accommodates presentations of fantasy and drama? What influence does our own personal attitude and disposition have on the young child’s reception of an imaginative presentation? Is it the language, the visual information or the energy within the presentation that dominates the influences upon the Child? How is the experience different for the child when media presentation and toy manufacture excludes an inter-personal presentation/sharing, and/or invitation to engage in interactive imaginative and creative play? D. Sloan describes his concerns as follows …..‘- through television, movies, literalistic picture books, detailed toys that leave nothing to the child’s own imaginative powers – children are made increasingly vulnerable to having their minds and feelings filled with ready-made, supplied images – other people’s images…..’ (Steiner, 1988:Forward)

Steiner presented that natural and undefined materials enhance free flowing creativity and give wide experiences and extensive opportunity for personal expression and intuitive exploration; thus expanding the learning experience beyond that which would have been gained by learning to perform a pre-structured activity and engage in consciously organized intellectual thinking.

Aesthetic and artistic experiences appear to be strongly influenced by the social aspects of music making, singing and live storytelling and associated theatrical presentation. Steiner suggests there is minimal need for correction at this age because the children’s own desires will facilitate assessment of results and aesthetic rhythms of routine, order and tidiness.

The Steiner kindergarten adults focus is on providing a natural and aesthetically pleasing environment with a joyful and child centred homely approach, where preconceived goals, plans, gains and ideas are secondary to the primary whole hearted celebration of creative living and spontaneous doing; where control of error has no place beyond practical applications related to the process of play, and learning is a wholly organic process in which ‘soul currents and bodily happenings interact’.(Steiner,1982:34) Aesthetic and artistic experiences are strongly influenced by the social aspects of music making, singing and live storytelling and associated theatrical presentation. Natural and undefined materials enhance free flowing creativity and give wide experiences and extensive opportunity for personal expression and intuitive exploration; thus expanding the learning experience beyond that which would have been gained by learning to perform a pre-structured activity and engagement in consciously organized intellectual thinking. In contrast to Montessori, Steiner appears to suggest that it is important that children are not encouraged to develop consciously organized strategies for intellectual thinking until after they start to lose their milk teeth in the seventh year. Steiner kindergarten adults focus on providing a natural and aesthetically pleasing environment with a joyful and child centred approach, where preconceived goals, plans, gains and ideas are secondary to the primary whole hearted celebration of creative living and spontaneous doing; where control of error has no place beyond practical applications related to the process of play, and learning is a ‘wholly organic’ process in which ‘soul currents and bodily happenings interact’ (Steiner,1982:34) The Steiner curriculum for children over seven years places importance on the consolidation of learning that is established after the child has had a night’s sleep. Initially a specific lesson content is presented/illustrated by the adult to the class. One or more days later the adult presents the same lesson content within activities where by the children gain their own experience of the content previously illustrated. Finally, on a subsequent occasion, the lesson content is presented in a way that facilitates that the children can engage in their own personal creative expression, exploration and experimentation.

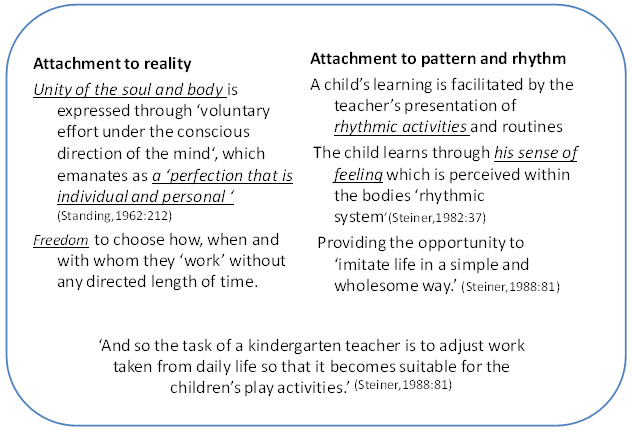

Montessori considered that the adults’ organisation of the classroom aids the child’s life and natural growth’. (LMC,1982:41) The young child’s willpower is motivated by what he wants and he uses his intelligence to organise according to his capabilities and the prompting of natural laws (rhythm) to formulate his interaction with the environment. (Montessori,1988:199). She presents that the children should be free to move about and express themselves spontaneously within the classroom throughout the day, and that this helps the children learn ‘active discipline’ through their own inner mastery of themselves. The adult’s only role of restraint would simply be to compassionately direct the activity so as to avoid disruptive actions that would offend, hurt, damage or disturb. She calls the adult the directress. However, this does not imply that she wishes the children to copy her actions or that she is there to correct a child if he does something wrong. Her methods emphasize the importance of imitation for the child during the early years. Unlike copying, imitation intrinsically involves the child’s desire to initiate a sensory experience, ‘enacted in deep earnest by the child in its play’. (Steiner,1988:80)

Montessori suggests that unity of the soul and body is expressed through ‘voluntary effort under the conscious direction of the mind‘, which emanates as a ‘perfection that is individual and personal‘.(Standing,1962:212) Montessori describes the first stage of development as the phenomenon of concentration.

‘Without concentration it is the objects about him which possess the child. He feels the call of each, and goes from one to another. But once his attention has been focused, he becomes his own master and can exert control over his world.’ (Montessori, 1988:197)

Subsequent to the development of concentration is that of perseverance. The state of concentration now embraces repetition which consolidates the child’s ‘ability to carry through what he has begun.’ The young child’s willpower is motivated by what he wants and he uses his intelligence to interaction with the environment according to his capabilities and the structural laws of physics. ‘But the child does not act from logic, he acts by nature.’Within an environment that provides the child with the freedom to follow his own inner forces, the child will focus his attention not on things themselves, but on ‘the knowledge he derives from them.’ (Montessori, 1988:198-199)The child wants to gain an understanding of how things work. He is seeking an intellectual form of knowledge.

‘If the adult presents her actions too forcibly she will attract the child’s attention to herself and not the action, the child then might copy ‘unessential peculiarities’ associated with unconsciously motivated impersonation. ‘(Standing,1962:218)

Montessori classroom organisation generally supports an emphasis on children working individually. The appropriateness of this approach would appear to be supported by Piaget in the following quote: ‘observation shows that up to a certain age, between 5 and 7 1/2, children generally prefer to work individually rather than in groups even of two.’ (1926:6) The Steiner classroom organisation presents a greater emphasis on social integration through informal group activities and rhythmic routines. Steiner proposes that at this time the young child should be encouraged to retain the dream like, fairytale disposition. He suggests adults should cherish the ‘magic remedy’: ‘reverence, enthusiasm and a sense of guardianship’ together with an outward manifestation of the adult’s nature. (Steiner,1982:30)

Montessori considered that a unity of the soul and body is expressed through ‘voluntary effort under the conscious direction of the mind‘, which emanates as a ‘perfection that is individual and personal‘.(Standing,1962:212)

The Sensitive Periods

Montessori methods are based on her belief that during the period 0-7 years children have critical learning periods that initiate learning behaviour. These ‘sensitive periods’ when the child shows a heightened vitality and pleasure are essential to normal development, and if the child is denied appropriate environmental stimulation, he will suffer limitations in his intellectual growth. (Montessori,1966&1988;L.M.C.,1982)Montessori describes these periods as: order, senses, language, walking, small objects and social aspects of life. (Montessori,1966:41;L.M.C,1982:13-14).The Montessori classroom provides a structured approach to learning with specially designed concrete didactic (intending to teach) apparatus for detailed sensory discrimination of size, shape, colour and shade, smell, sounds and musical tones and semi-tones which includes a structural control of error. (L.M.C,1982;Montessori,1967:100-103)

The following section describes in greater detail each of Montessori’s ‘sensitive periods’ with some further comments describing related aspects from Steiner’s perspective.

Steiner and Montessori appear to agree that the early years (up to Seven years) are predominantly involved with the development of sensory reception, perception and assimilation. During the first three years the child focuses on exploration in order to gain highly detailed sensory information and thereby develop knowledge understanding of their environment. Steiner presents that during the first three years, the child is learning to ‘walk, speak, and think ‘ and ‘to a large extent, the foundations are being laid for a person’s whole or in our life and configuration .’ (Steiner,1988a30&44)

Montessori methods are based on her belief that during the period 0-7years children have critical learning periods that initiate learning behaviour. These ‘sensitive periods’ when the child shows a heightened vitality and pleasure are essential to normal development, and if the child is denied appropriate environmental stimulation, he will suffer limitations in his intellectual growth. (Montessori,1966&1988;L.M.C.,1982) Montessori describes these periods as: order, senses, language, walking, small objects and social aspects of life. (Montessori,1966:41;L.M.C,1982:13-14).The Montessori classroom provides a structured approach to learning with specially designed concrete didactic (intending to teach) apparatus for detailed sensory discrimination of size, shape, colour and shade, smell, sounds and musical tones and semi-tones which includes a structural control of error. (L.M.C,1982;Montessori,1967:100-103)

The following section describes in greater detail each of Montessori’s ‘sensitive periods’ with some further comments describing related aspects from Steiner’s perspective.

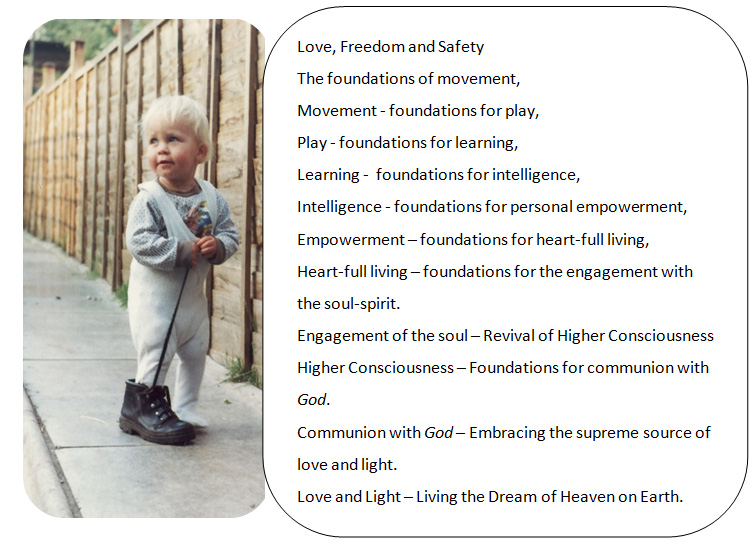

ORDER(1st– 4th year);-

‘The law of nature is order and when order comes of itself, we know that we have re- entered the order of the universe.’ (Montessori,1998:261)

Order in the child’s external environment helps him to ‘categorise his perceptions and to make sense of the world‘. (L.M.C.1982:14) This period is particularly evident when the child has a passionate interest in the order of things both in time and space and learns to move objects from one place to another. He may at this time develop strong attachments for specific aspects of order. (Riley,2003)This sensitive periods last for about two years and is most prominent during the child’s third year, when the child has a passionate interest in the order things both in time and space. This brings him into a ‘ritualistic’ positivity and seemingly ‘tyrannous’ levels of protest, when the accustomed routine or order is (from a child’s point of view) meaningless altered. Montessori describes the young child’s need for order and stability as a genuine necessity because he is ‘constructing himself out of the elements of the environment ‘…… ‘the child ‘is striving incessantly to bring this bewildering universe, as he knows it, into some sort of order. No wonder it upsets him when that minimum of order which he has discovered becomes destroyed.’(Standing, 1962:126)

The children’s choice of activities within the Montessori classroom is organically regulated by the emphasis on the child’s responsibility to return apparatus to its correct place. The storage of each item is presented in a structurally correct manner and even the youngest children can quickly discern the appropriateness of what they choose from the wide range of equipment and materials available within the classroom. This also encourages each child to make a reasonable and suitable commitment to the choice of activity through associated standards of tidiness.

Steiner presents that the young child’s relationship to a sense of order is met by the organisation of rhythm, repetition and daily routines within the kindergarten.

SENSES (1st – 9th year)

During the early years the child subconsciously selects how he responds to environmental stimulation associated with hearing, seeing, touching, tasting and smelling. Montessori methods place a particular emphasis upon the importance of training the child to refine, improve, and make sense of sensory perception and discrimination. The Montessori didactic (intending to teach) apparatus promotes sensory-motor activities which develop skills of differentiation within each of the five senses, imprinting thought upon the brain through ‘sense-perceptible eurhythmy’. (Steiner,1982:41)

Steiner presents that before the change of teeth the young child is ‘essentially an ensouled sense organ entirely given over in a bodily religious way to what comes towards it from the surrounding world’and that sensory experience ’permeates the child’s entire organism.’ He suggests that whatever is happening in the child’s environment is wholly and subconsciously received by his senses and thereby also affects his soul and spiritual development.(Steiner,1988:75,40)Steiner schools today present that watching television does not meet the sensorial needs of the young child and, furthermore, prevents the young child from receiving what he needs in order to have his physiological needs met appropriately. Steiner emphasises the need to learn through movement and multi-sensory experience; watching TV does not involve any body movement and presents an unnatural dominance of visual stimulus, much of which may not have any personal meaning within the child’s own reality. Similarly how is the experience different for the child when media presentation and toy manufacture excludes an inter-personal presentation/sharing, and/or invitation to engage in interactive imaginative and creative play? D. Sloan describes his concerns as follows …..‘- through television, movies, literalistic picture books, detailed toys that leave nothing to the child’s own imaginative powers – children are made increasingly vulnerable to having their minds and feelings filled with ready-made, supplied images – other people’s images…..’ (Steiner, 1988:Forward)

- Childs (1991) cites Steiner’s presentation that –

‘The human being is citizen of three worlds. Through his body he belongs to the world which he also perceives through his body; through his soul he constructs for himself his own world; through his spirit a world reveals itself to him which is exulted above those by others.’

SMALL OBJECTS (2nd – 5th year)

This period is illustrated by the child’s urge to use his five primary senses to discover in great detail information about his environment. During this period the child examines small objects or specific small parts of an object and thus he develops his sensory knowledge and detailed awareness and understanding of his world.

Montessori and Steiner both describe the young child’s intense curiosity in detailed aspects of the natural world, music and communication.

WALKING (2nd -5th)

Montessori describes walking as a skill that needs practice and when self-motivated the child has high levels of stamina and endurance.

Steiner describes how learning to walk helps the child establish its ‘equilibrium with the physical world surrounding it’. When learning to walk the young child is seeking physical balance, but when movement of the arms and hands can be independently organized from the legs and feet a child learns to experience ‘the principles of statistics’ and the ‘dynamics in one’s own inner being’.

‘Through the fact that the movements of arms and hands have become emancipated from those of the legs and feet, something else has happened. A basis has been created for attaining a purely human development.’

Steiner goes on to describe that

‘…..speech has to be developed on the basis of the right kind of walking and of the free movement of the arms…… the beat-like, rhythmical element of the moving legs works upon the more musical-thematic and inward element of the moving arms and hands.’ (Steiner,1988:31-32)

He also equates the faculty of autonomous movement with the consequential development of language and thinking, and this he suggests facilitates the foundations for good speech and language development. This association between walking and speaking through the body’s rhythmic system is the foundation to Steiner’s development of eurhythmy.

LANGUAGE(Birth to 5th year)

During the first five years the child develops a basic level of language competence. Steiner presents that learning to walk initiates a child’s faculty of speech and from the faculty of speech the ‘new faculty of thinking is gradually born’. He also suggests that the language experiences the young child receives from his environment are deeply and unconditionally received; and affect all aspects of his inner state of being. A child energetically receives everything that is presented verbally, emotionally and spiritually from the outside environment.(Steiner,1988a:49-50)

Montessori presents that the language skills acquired during this sensitive period for language are significantly important for all further language development.When illustrating the use of a specific piece of sensorial apparatus Montessori recommends that adults use the ‘Three Period Lesson’ presented by Eduoard Seguin.

1st Period: The vocabulary that is specifically presented by or associated with the apparatus.

2nd Period: The child is asked to use the apparatus to indicate the meaning of the vocabulary that the sensorial apparatus illustrates.

3rd Period: The child is asked to provide the language that describes the information presented within the sensorial apparatus.(LMC,1982:43)

Montessori presents that the language skills acquired during this sensitive period are significantly important for all further language development and competence. Steiner presents that the rhythmic movements of walking enhance the development of speech and from the faculty of speech, the ‘new faculty of thinking is gradually born’. (Steiner,1988:49) They both suggest that the language experiences the child receives from his environment are deeply and unconditionally received and affect all aspects of his inner state of being. A child energetically receives everything that is presented verbally, emotionally and spiritually from the outside environment.

Steiner schools place a strong emphasis on story-telling and live music making – books, TVs and computers are not considered appropriate in the Kindergarten classes. There are many unresolved issues related to our knowledge and understanding of how the medium, style and quality of presentation influences the child’s ability to appropriately distinguish between real and fantasy.

The greatest disagreement between the Montessori and Steiner methods appears to be focused on when to teach the children to read and write.

Steiner presents that children should not be taught to read or write before they start to lose their milk teeth for to do so would lead the child into ‘abstractions prematurely’ and ‘hardening’ of his natural human nature. Then he suggests that the letter shapes should evolve from painting and drawing and thereby remain ‘something more concrete than reading’. (Steiner,1988:85-86)

Montessori presents that children in their fifth year found for themselves a new language, a visual system of written symbols which provided an effective form of language communication. Montessori found that the children’s spontaneous desire to learn how to write came several months before they went on to learn to read. Montessori discovered that it was the children who had the opportunity of learning the shapes of the individual letters by feeling them and knew their corresponding phonetic sounds, who moved with dramatic suddenness into writing. Montessori designed carefully structured sensorial materials to illustrate and facilitate phonic word building and simple whole word recognition. Both Montessori and Steiner advocate that learning to write precedes reading through a combination of different methods, and that literacy skills should emanate from a child initiated desire and child centred approach to learning.

SOCIAL ASPECTS (4th – 7th year)

In contrast to the first three years when the child’s whole body is deeply influenced by all the sensory experiences presented within his surrounding environment. Montessori and Steiner both suggest that during the first three years the child is impulsive and generally not emotionally or socially influenced by his external environment. This sensitive periods of social development starts around the age of three when the child becomes aware of their independence and their choice to cooperate with others. Montessori suggests this ‘is not instilled by instruction, that it comes about spontaneously and is directed by an unconscious power’(L.M.C.: 1982:15)and thereby ‘following the method of nature’.(Standing, 1962:218)The child follows an inner impulse while ‘guided by his inner need’. Montessori and Steiner consider imitation to be a predominant aspect of early learning when it is inspired by the child’s own initiative,to give up his natural child related response, in orderto imitate the adult disposition; to gain personal experience of that which is activity illustrated by another person.Montessori calls the adult the directress, however, this does not imply that she wishes the children to dogmatically copy her actions or that she is there to correct the child if he does something ‘wrong’. The Montessori adult provides guidance and suggestions only when the child is unsettled or specifically asks for help. The adult respectfully, calmly and patiently provides the child with the required help by example, so that her presence does not cause the child to lose contact with his own motivation, self direction movements and experience. Information, illustrations, and guidance are presented to the child in small consecutive steps.

Montessori and Steiner describe the classroom as a community where the children cooperate for the ‘honour of their community’, each doing his part without hope of reward with a ‘sense of solidarity not instilled by instruction completely extraneous of any form of emulation, competition or personal advantage, a gift of nature.’(Montessori,1998:213& 130)

Both describe the importance of organically motivated Imitation—routine tidiness,–gentle atmosphere—kind motherly interpersonal relationship between adults and children. Approaches to antisocial and or disruptive behaviour are based on motherly intimacy, informal styles of sharing which are non invasive, non judgmental, gentle and kind with an emphasis on by example.They suggest there is no need for correction at this age because the children’s own desires and aesthetic rhythms of routine, order and tidiness will facilitate assessment of results and inner disciplines. Mutual appreciation and respectbetween adult and children helps the children find independence and obedience through organised learning.Both present that the child under the age of Severn does not distinguish between good and evil and small children should not be ‘confronted with such problems he accepts and believes everything, the only evil that he can imagine is naughtiness which is defined externally by adults who identify the behaviour as unacceptable for reasons which are usually beyond the child’s own inner comprehension. Children have at this age an inner sensitivity that initiates their spiritual senses that guide his whole being and initiate, when moved by these inner feelings, simple natural sharing of kindliness and compassion.

They also present that during this sensitive period all socially related language perceived by the child from his environment is inwardly felt, and thereby affects the whole life of such a child, and later turns towards the outer world through his own language.

Montessori describes the adults’ role as keeper and custodian of the environment offering an invitation to learn. The adult holds a spiritual relationship with the children and through this she serves their needs and keeps them company in their learning. She must be careful not to interrupt when the children are engaging with concentration. Group activities in the Montessori classroom are optional when directed by the adult, and spontaneous when created by the children’s own activities and shared interests.

‘If the teacher meets the needs of the group of children entrusted to her, she will see the qualities of social life burst surprisingly into flower, and will have the joy of watching these manifestations of the childish soul.’ (Montessori,1998:257 )

Both Steiner and Montessori describe the young child’s ability to ‘transcend the senses’ (Montessori1967:296) and lovingly embrace a soul based spirituality associated with concepts of God the Father, sacred occasions and places of worship suggesting that children acquire, almost imperceivably, a knowledge of religious things. Both present that the child under the age of seven does not distinguish between good and evil and his own experiences of childhood naughtiness may be burdened with unfair and oppressive judgments, if adults are not mindful of the child’s innocent and highly receptive disposition.

Steiner and Montessori pedagogy appears to predominantly be in agreement with most of the basic issues of early childhood learning and the heart-full simplicity with which children embrace their natural affinity with joy, love and spirituality expressed as a love of:-

- Free play,

Steiner presents that it is the enactment of the child’s will rather than intellect that formulates the child’s early passionate enthusiasm for learning….‘The child wants to be active simply out of an inborn and natural impulse. Play activity streams outward from within.’(Steiner, 1988:80)

- Working together, Bernard when citing Maslow presents that ‘…when pupils feel that they are part of a group, desirable and purposeful learning activities are facilitated.’ (Bernard,1965:248)

Creativity and beauty

However, the Steiner and Montessori styles of environmental care and support appear to be weighted from different perspectives. Steiner appears to emphasize the abstract aspects of creativity and communication. Montessori appears to emphasize reality and sensory discernment of the concrete and a more structured approach to learning activities.

| CONCRETE | ABSTRACT |

| Consciously organized | Subconsciously organized |

| Voluntary actions | Involuntary responses |

| Exploration, creativity, planning, problem solving | Intuitive, spontaneous, impulsive, imaginative |

| Self-discipline ‘plan, do, review’ High Scope | Cultural and Social discipline |

| Kinaesthetic sensory experience Sensory Perceptual development through the senses | Absorbing the environmental surroundings Whole- body perception through the rhythmic system |

| Predominantly auditory and visual awareness facilitating ‘Cognitive’ organisation of all sensory information | Aesthetic and feeling based awareness facilitating ‘Conceptual’ understanding. |

| ‘Pretend’ play: imaginative creativity based on real possibilities: role play e.g. driving a fire engine, feeding the baby or re-enactment of experiences e.g. Having a bath, being in a boat, doing the sweeping. | Fantasy play: imaginative creativity incorporating impossible scenarios, fairies, unicorns, impossible solutions – ‘the dog jumped over the house’. |

[Conceptual understanding – a general notion, thought, opinion or idea about a state of being.Cognitive understanding – the faculty of knowing or perceiving the natural relationship associated with origin.]

Steiner presents that ‘up to the seventh year the child is permeated on the whole more by sculptural’ (all that is seen – visual/visualised) ‘and less by musical forces’ (Steiner,1982:19) (all that is heard/felt). During these years the sculptural concrete element works together with the abstract music and speech elements united through the ensouled spirit of the child.

Montessori suggests that unity of the soul and body is expressed through ‘voluntary effort under the conscious direction of the mind‘

If learning involves the reception, organisation and integration of concrete and abstract environmental experiences, then the concrete and abstract nature of the environment can be explored in relation to learning and ‘Balance in Teaching’ (Steiner,1982) can be addressed.Such that the abstract can be expressed and the concrete can be felt. With the freedom to follow his own inner forces, the child will focus his attention not on things themselves, but on ‘the knowledge he derives from them…….the child does not act from logic, he acts by nature.’ (Montessori, 1988:199)

| Abstract. | Learning. | Concrete. |

| External physical interaction (experiential activity) | Consequential action | |

| Social interaction | Internal disposition (Personality) | Subtle awareness |

| Spontaneous interaction | state of being (individuality) | Acquiring Independence |

| Movement and creativity | attention and concentration (Worldly interaction) | Doing and Thinking |

| The rhythmic system -intuitive feelings | Internal neurological activity | Sensory-motor discernment- Integration of the senses |

| Patterns and possibilities | Intrinsic physiology | Structure and information |

| Passion and improvisation | Focus of attention and quality of engagement | Practise and purpose |

| Symbols and sounds | memory | Visual imagery and patterns |

| Imagination, intonation and verbalised expression of thoughts | Language and communication | Body language, sign language, facial expressions and the mechanics of speech production |

| Aesthetic appreciation | Personal Disposition | Emotional response |

| Creativity through arts and crafts- fine motor control | Understanding cause and effect- knowledge | |

| Conceptual appreciation | Cognitive differentiation | |

| The journey of development, rhythms of change | Detail and differences, parts to make a whole | |

| Celebration and the development of social competence and cultural appreciation. | Motivational Disposition | Personal responsibility for the development of academic skills ( e.g. Literacy and numeracy) |

| Expression through the arts, language and music. | Scientific exploration, application to task related apparatus, method and results. | |

| Authenticity and intuition | Concentration and focus | |

| Social competence | Self esteem | |

| Spiritual awareness | Development of skills |

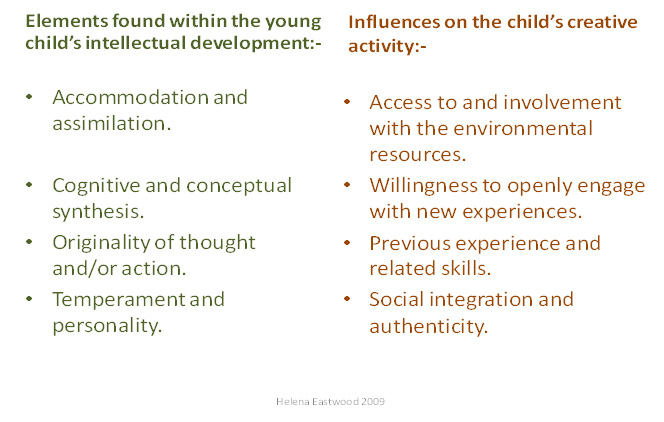

If the creative element of intelligence involves something beyond that which has been experienced and thereby incorporates a union of real (concrete – perceived through the body senses) and imaginary (abstract – beyond what is at present directly or indirectly experienced), one might present that authentic creativity has to include an element of inventive inspiration. Steiner appears to emphasize this development during the 3-7 years, whereas Montessori appears to emphasize the acquisition of knowledge based on sensory differentiation within the real environment.

In the example below the author illustrates how the language associated with a classroom activity, such as, a short story, can give a different weight of emphasis upon the elements of Real(physical, mental and emotional experience)

Pretend(re-enactment of physical, mental and emotional experience)

Fantasy (communication of thoughts and representational actions beyond structural physical, mental and emotional experience)

Oncea little bird fell out of his nest and was very sad. He was crying, when a little fairy called Melodycarefullypicked him up. She flewright up into the tree branches and put the little bird back into his nest.

One morning Peter was having a lovely time playing in the mud at the back of the garden. Later that day his mum went outside to hang the washing on the linebut she could not find the pegs anywhere. She was just about to call Peter for help when she noticeda very strange bush sticking out of the mud in the corner of the garden.This bush had grown pegsinstead of leaves; they were all different colours and sticking out in all directions.

This example illustrates how a Steiner style of emphasis might be on the fantasy element of imaginative play, and a Montessori style of the emphasis might be on the pretend element of imaginative play.

Steiner appears to emphasize the importance of creativity and imagination and their positive influence on the child’s overall development of intelligence. This is supported by evidence that illustrates notable qualities of intelligence illustrated by those with a creative disposition and a suitably supportive environment. Bernard identifies these special qualities as follows: fluent language and expression of ideas, flexible and adaptive, adventuresome, divergent and inventive thinking, good use of memory and application to new situations, humour and playfulness, openness to feelings, high levels of incentive and curiosity, tolerance and wisdom, nonconformity, strange and obscure ideas, drive to go beyond normal expectation, appreciation of theoretical and aesthetic qualities. (Steiner,1965:88)

Duffy (2006) goes describes creativity as something considerably more than imagination and her definition includes: relating past learning to new situations, non-traditional approaches to problem solving, thinking beyond the information given, connecting and rearranging information from different sources, originality and adaptability.

‘Through a curriculum rich in creative and imaginative opportunities young children have the opportunity to develop skills, attitudes and knowledge that will benefit all areas of their learning and development.’

Duffy also suggests that creativity and imagination are not something that can be taught or measured because it comes ‘from the human ability to play’ (Duffy,2006:12-13) and it should be viewed as a long-term involvement throughout life.

Bernard cites Piaget and suggests that prior to the age of 6-7 the child is ‘unable to maintain a simultaneous awareness of a whole and a part’ and his thinking is tied to his own physical activities and ‘simple forms of symbolic reference’. This Piaget calls the ‘Preoperational Stage’. Between the age of six and seven the child moves onto the next stage of thinking, ‘concrete operations’. This allows him to develop reasoning and thereby consider ‘the implications of actions without having to carry them out.’ The child now has an ability to mentally rehearse, imitate and imaginatively represent external situations within the mind.(Bernard,1965:88)

Piaget’s theory appears to support Steiner‘s philosophy which, during the kindergarten years 3-7, avoids teaching methods and curriculum that require concrete operational thinking and reasoning skills. In keeping with Piaget’s theory the Steiner curriculum after the age of seven changes to a more formal topic based style that embraces and encourages a more structured approach. Steiner encourages class adults to integrate the spontaneous creativity of the preoperational stage with the development of concrete operational thinking, and reasoning. At this age Steiner’s pedagogy emphasises the more concrete aspects of learning, and thereby illustrates a large degree of agreement and compatibility with the Montessori project approach to education at this later age.

The author has summarised the two philosophies as:-

Steiner: The crucial nature of the child’s early years is that the body, soul and spirit are in complete unity. The natural rhythms and sensorial experiences from suitably child appropriate daily life provide simple and wholesome real life experiences for the young child’s ‘sense directed’ desire to imitate. Inner spiritual forces facilitate that the child’s imitative responses include ‘artistic impulses’ and allow the child to respond in an entirely individual way, unfolding its own soul activity. ‘The art of education must proceed from life itself and not from abstract scientific thought’ (Steiner, 1988:5) and we must protect the child from being absorbed too strongly or too rapidly into the outer world and the influences of intellectual education.(Steiner,1982:29,46,47;1988:24;Childs,1991:67)Steiner emphasizes the balance in teaching, which is listening and watching (that which comes inward from the outside) and the autonomous activities of doing(that which isoutward expression from within). It is the enactment of the child’s will rather than intellect that formulates the child’s early learning. Steiner describes children’s learning as a ‘whole organic process, in which soul currents and bodily happenings interact’. (Steiner,1982:34) Steiner pedagogy is facilitated through the personality of the adult. Child’s describes Steiner’s ethos as ‘Imbue thyself with the power of imagination’…. ‘Have courage for the truth’..and…. ‘Sharpen thy feeling for responsibility of soul.’ (Childs,1995: 61)

Montessori: Freedom to play within a structured environment through which the child will discover the joy of work. (L.M.C.1982:25; Standing,1962:42;Montessori,1966:193-198) The Montessori classroom emphasizes the practical aspects of living and doing. Within an environment that provides the child with the freedom to follow his own inner forces, the child will focus his attention not on things themselves, but on ‘the knowledge he derives from them…… But the child does not act from logic, he acts by nature.’ (Montessori, 1988:199) She presents that each child has cycles of activity that should be allowed to be worked through and completed without interruption, and in this way the child truly learns according to his own individual needs and capabilities. When the environment provides a scaffolding (Roopnarin&Johnson,1987:374) for consciously organized sensory differentiation and discernment it creates a platform for the child’s development of awareness and organisation of knowledge and understanding. Montessori suggests that between the ages of three and six successful completion of tasks will normalise a child’s powers of concentration, intelligence and self-discipline. (Montessori,1988:182,188,243)

Independence and initiative: Play is a child’s ‘work’Montessori emphasized the concrete aspects of living and doing. She provided specialized concrete didactic apparatus with a structural control of error. This equipment encouraged detailed sensory discrimination of size, shape, colour and shade, smell, sounds, musical tones and semi-tones.

The child’s freedom can be directed by the adult’s careful preparation and organisation of the environment.

Play is a natural inborn impulse: Steiner Kindergartens provides natural and undefined materials which are considered supportive to free play and natural flowing creativity.

That gives wide experiences and extensive opportunity for personal expression and intuitive exploration; thus expanding the learning experience beyond that which would have been gained by learning to perform a pre-structured activity and engage in consciously organized intellectual thinking. The adult organises the children’s participation in music, craft and cooking activities on a daily basis.

Comparing Steiner and Montessori Philosophy the chart below summarises differences:-

| Steiner | Montessori |

| 3-7 years should be taught as a family group | 3-7 years should be taught as a mixed age group |

| Play is a natural inborn impulse | Play is a child’s ‘work’ |

| Natural environments nurture the child’s soul and spirit | The child finds independence through organised learning |

| The child learns through his sense of feeling which is perceived within the bodies ‘rhythmic system’ | Child directed learning with maximum freedom of choice for each individual child |

| A child’s learning is facilitated by the adults presentation of rhythmic activities and routines | The child’s learning is facilitated by the adults presentation through example and specific illustration |

| Social play and being part of a group, to whom different activities are presented within a familiar environment and routine | Freedom to choose how, when and with whom they ‘work’ without any directed length of time. |

| Mutual admiration and respect for the guardianship role of the adult | Mutual appreciation and respect between adult and children |

| Looking to the adult for information, guidance, instruction and boundaries | Confidence to ask the adult or others for information, help and guidance |

| Children enjoy a wide variety of opportunities for interactive play and group participation | Children enjoy working alone on their individual mats and learning specified skills. |

| A specified group of children sharing as a small community with its own ‘home base’ | Individuals working together as a team caring and supporting each other |

| Mastery through child initiated imitation and rhythmic repetition | Mastery through focus , concentration and repetition |

| feeling through sensorial experience | Sensorial experience through doing |

| Joyful activity | Experiential experiences |

| Fantasy and creative expression | Discovery and application to tasks |

| Passion and aesthetic appreciation | Knowledge and understanding of the physical world |

| Exploration and experimentation | Enquiry and purposeful activity |

When the education environment is focused on child-directed learning the child himself has the opportunity to balance the elements of freedom and self-discipline, abstract and concrete, autonomous and group learning.

Development ofAssimilation and Accommodation

-learning through environmental stimulus

The following four consecutive stages are established during childhood development:-

- Sensory stimulus– assimilation of sensory information presented by the environment to the physical sensory receptors.

- Concrete integrationof sensory information – physical multi-sensory enrichment acquired through child directed exploration and experimentation. Experiential experiences, constructional sensory-motor activity. Memory.

- Abstract thinking– conceptual understanding; feeling – energy, moods, disposition, attitude, willingness, desires, and recall.

- Creativity- imaginativeintegration of a, b, and c (sensory, concrete, and abstract) with authentic and unique aspect of personal individuality. The heart and soul connections that nurture, dreams, morals and beliefs, and initiate Spiritual experiences of reverence, compassion, gratitude and appreciation.

A four day experience of play and learning on a natural beach environment is described below as an example of the above theory in practise:-

Day one (a) Mobility – sensory exploration, assessment of environment, testing and establishing boundaries, knowledge of the environmental geography.

Day two (b)

Increasing the sensory experiences by physical efforts that initiate gross motor interaction.

For example running away from the waves; splashing, diving, sitting in the shallow waves; throwing sand, digging a hole, covering yourself or someone else burying them in the sand; playing chase games on the sand, or in the water, stamping on shells and worm castings, collecting seaweed or driftwood for a fire, collecting other items from shore line old rope containers etc.. Sensory experiences upgraded to a maximum, exploring environmental and social aspects of control and testing boundaries. Excitement and enthusiasm, over enthusiastic, attention seeking /challenging behaviour seeking/engineering stronger sensory stimulus, a strong sense of action and reaction.

Day three (c)

Relating to the environment through creative activity.

Sand structures building and decorating them sandcastle waterways and three dimensional structures serving a waves with the with or without the search for learning to swim playing catch on the beach and or in the sea constructing a sun shade tent or winter break from sticks and stones and hotel building is and village designing.

Day four (d) A day of relaxation, a heart felt accommodation of the previous three days experiences, recap and remembering , recall and meditation. Spiritual experiences of reverence, compassion, gratitude and appreciation.

Much of children’s play activity today is occupational rather than educational. Their activities are focussed on and/or dominated by the reception of sensory stimulus described above in (a). The child’s physical activity is either minimal or directly related to the repetition or prolonging of a specific sensory experience. Also we have such a highly stimulation environment much of a child’s day can be occupied by acclimatisation i.e. getting familiar with the environmental stimulus in ever changing environments. The child thereby gains a large amount of sensory input but little opportunity to actively explore in more detail the context and interrelated nature of their different sensory experiences. Because children by nature need to be physically active they establish a repertoire of occupational responses which provide opportunity to move within the context of prolonged strong sensory stimulation, e.g. the young child watching TV may suck a blanket or manipulate a cuddly toy, older children play on computer games that require fast repetitive button pushing movements. The author describes these predominantly receptive sensory occupations as entertainment. Entertainment here describes situations that hold a child’s focus in the first level of learning that of (a)

Some children may be suited to the more abstract imaginative and creative Steiner approach. Others may feel more at ease with the concrete and structured Montessori methods. However, all will hopefully receive a rich, gentle and nurturing physical environment that encourages child directed learning and natural child centred activity.

Children do not receive any specified educational help for learning to stand and walk, communicate and talk, feel and think. What then is the responsibility of the adult carer beyond that of providing a warm hearted, compassionate and appropriate guardianship over the child’s spontaneous and joyful desire to learn through play?

When the environment is focused on child directed learning – the child himself has the opportunity to balance the elements of: freedom and discipline, abstract and concrete, and autonomous and group learning.

The author feels the most influential aspect within educational care is the adult’s own inner feelings towards each individual child;‘The adults feelings are certainly the most important tools of education.’ (Steiner 1982:18)Maybe it is this, which Steiner and Montessori advocate so highlythat is the real issue related to the children’s positive learning experiences, rather than the teaching methods or the classroom environment,

Maria Montessori and Rudolf Steiner have used their own personal experience as adults to develop a pedagogy that addresses fundamental issues they (together with other pioneers in education) believe are paramount to children’s wellbeing, development and learning. The summary below describes what is thought to best facilitate children’s natural play and learning:-

– illustrate care, love and understanding

– leave a child undisturbed when he is engaged in concentrating on a chosen activity

– gives each child freedom to make his own plans, choices and decisions.

– illustrate by example how to do things, what different objects do, and what they are used for.

– provides a child friendly interesting learning environment.

– present difficult tasks broken down into small consequential, step by step actions

– gain a deep knowledge and understanding of the individual child’s personal qualities, passions, skills and temperament.

The Steiner describes and the three principal human virtues and as: willing gratitude; the will to love; the will to do one’s duty. The adult must add to this the matter of ‘knowing how to adapt oneself to the individuality of the growing child.’ And what content and to bring to their pupils in their various ages and stages.(Steiner,1988a:127) Steiner emphasizes ‘the balance in teaching’ which is a moment by moment relationship between the adult with the individuals and class is a whole, such that no amount of experience or knowledge of external pedagogy can create because the best teaching comes from spontaneous and compassionate authenticity . Steiner does not appear to present his pedagogy as an external and impersonal role model but rather he wishes to enhance the personality of the adult within a style and foundation framework that allows everyone to feel relaxed within their own unique personality and subsequent worldly interaction.

The Montessori methods appear to be based on ‘freedom within a structured environment’ within which Montessori presents that the child will discover the ‘joy of work’. She suggests that play and learning are the child’s work, and ‘that “normalisation” through work is most likely to succeed between the ages of three and six years. During this time it is suggested that successful completion of tasks will ‘normalise’ a child’s powers of concentration, intelligence and self-discipline during this early formative period (L.M.C.: 1982:25)Montessori seems to suggest the adults role is to organize an environment that facilitates natural learning through concrete multi sensory experience. And that carefully structured didactic apparatus and empowers the learner and encourages confidence that later supports child directed learning. That it is the adult’s role to teach through illustration rather than directing the child into copying the adult. Nothing the child does is considered wrong and the child is free to experiment within his learning environment, however, he must nevertheless learn appropriate care and behaviour that successfully accommodates that objects are normally used within the context of their designed purpose, positive social interactions (e.g.turn taking and sharing), and returning items to their ordered/tidy disposition at the end of the free-play period.

This controlled freedom provided by learning materials and apparatus helps the child develop self-discipline as well as: sharing, respectful interactions, and an ability to value and appreciate the different environments and their respective learning potential.(L.M.C.: 1982:30)

The adult’s ability to facilitate or obstruct the child’s Social and environmental wellbeing requires the ability to find a balance that maintains harmony and encourages personal empowerment for example :-

- Enrichment versus over-stimulation

- Inspiring versus overwhelming

- Encouragement versus superiority

- Illustrating creativity versus authentic creative interaction

- Sharing versus entertainment

- Copied learning versus co-operative learnin

- Sharing versus entertainment

- Illustrating creativity versus authentic creative interaction

- Encouragement versus superiority

- Inspiring versus overwhelming

The skills related to the above and a person’s ability to scaffold a child’s natural learning potential are directly related to a conscious understanding or intuitive perception of what Vygotsky describes as the child’s Zone of Proximal Development.

The Zone of Proximal Development ( ZPD)

Meadows (2006)cites Vygotsky’s description of the child’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) which describes the area of learning potential between the lower level of what the child can already ‘do independently’ and the highest level of ‘what the child can do with such assistance i.e. demonstrations, prompts or leading questions.’ (Meadows,2006:309) Meadows (2006) also indicates that a ‘diagnosis of the ZPD is necessary both for a full assessment of the child’s abilities and for the optimum targeting of instruction.’ (Meadows,2006:308-9) Vygotsky suggests that good instruction: identifies ‘a certain minimal rightness of function’; spontaneously develops concepts that ‘confront a deficit of conscious and volitional control’; and accommodates the ‘social and cultural nature’ of the individual child.(Vygotsky,1986:188-189)

The lowest threshold at which the ZPD begins

- The Zone of Actual Development (ZAD)(MacNaughton,2004:334) Learning already established – present level of ability, strengths and weaknesses, established approaches to thinking and learning. The ‘social and cultural nature’ of the individual child’s development and corresponding ‘ripening functions’ that have not yet ‘fully matured’.(Vygotsky,1986:189)

- Previous Play Experience – free play with the materials in advance, direct or indirect association with others who are successfully illustrating a higher level of skill/ attainment. Hughes (1991) cites research by Sylva who found ‘the children who either played with the materials in advance or watched an adult solve the problem became more successful problem solvers’ and appeared to be more ‘highly motivated’ and persistent than those in the observation group ‘who either solved the problem immediately or simply gave up’. (Hughes,1991:186)

Utilisation of The Zone of Proximal Development

Lytton (1971)cites the work of torrents(1965) whose research illustrated that children in kindergarten and infant classes whose adults ‘expressed strong creative motivation’ improved more than the children with teaches who were more critical and controlling. (Lytton,1971:107) When engaged in teaching within the child’s ZPD the adult may consider the following in relation to ‘creative teaching’ (Williams,2003:111) and ‘good instruction’(Vygotsky,1986:188-189)

- Scaffolding– Williams(2003) cites Vygotsky and Bruner – ‘Scaffolding refers to the arrangement of activities through which the adult or the more expert peer assists the learner to achieve goals, which would otherwise be beyond him or her. Scaffolding is a flexible and child centred supportive strategy. ‘As the child masters new skills the adult is able gradually to remove the scaffolding.’ (Williams,2003:110) Meadows(2006)proposes that ‘an early history of good scaffolding… sets up… learners to become their own scaffolders.’(Meadows,2006:312)

- Joy – ‘helping children to experience joy in a commitment to learning’ within ‘a familiar environment’ relevant to the child’s previous knowledge, experience, understanding and ‘holistic nature of learning’, existing confidence and independence and his own way of thinking. (Williams,2003:111-112)

- Freedom – ’freedom of observation and of judgment exercised on behalf of purposes that are intrinsically worthwhile……. freedom of thought, desire, and purpose.’(Dewey,1938:69)

- Emphasis upon intelligent activity, ‘information processing’,(Meadows,2006:217) rather than the means to an end product. The ability to inhibit impulses; conceive the consequences of their actions; visualise the future. (Fisher,1990:139)

‘it is also essential that the new objects and events be related intellectually to those of earlier experiences’. The adult selects new experiences that have the potentiality of ‘stimulating new ways of observation and judgment’(Dewey,1938:90)

- The Act of Discovery(Bruner,1973:401)- curiosity and the ability to embrace the surprise phenomena (Bruner,1973: 209), flexible responses to environmental experiences, inventive activity, internal motivation to interact, investigate and persevere.

- Social and Cultural Experiences – ‘…reciprocal give and take, the adult taking but not being afraid also to give. The essential point is that the purpose grows and takes shape through the process of social intelligence.’ (Wood,1998:85)

- Decentering – ‘Decentering, which is a prerequisite for the formation of the operation, applies not only to a physical universe ……but also necessarily to an inter-personal and social universe…..’(Piaget,1969:95)Reversibility and reciprocity(Piaget,1969:159); sharing and division; symmetry; inversion; to undo.

- Discernment and Choice – intrinsic and extrinsic motives (Bruner,1973:406) and adult facilitated activities that provide useful connections and combinations, new perspectives and a quality of invention through organised discernment and choice. (Bruner,1973:210)

- Planning – identification of ‘essential information’, ‘processing capacity’, (Meadows,2006:129) material requirements and levels of ability.

- Principles of Classification – defining properties, inference of identity and relationship, categorisation, adaptive significance, equivalents, grouping etc. (Bruner,1973:219)

- Symbolic Representation – visual imagery, signs and symbols, gestures and body language, communication through movement or sign language.

- Utilising Information – inductive learning: organisation of diverse information, reversibility, alternation, probability, utilisation of formal coding systems, inference and proposition, equivalence, retrospective and prospective considerations and systematic organisation. (Bruner,1973:220-221)

- Communication of Knowledge – comprehension, ‘sensory-motor schemes lead to those new combinations and internalizations that finally make immediate comprehension possible in certain situations.’ (Piaget,1969:12)and action – ‘acting upon objects in space and time’; concepts and procedures(Wood,1998:17,13)

- Learning as a three period lesson.

This appears as part of the Steiner lessons and is organically incorporated within the following Steiner method: The first lesson-involves a multisensory presentation of information. The second lesson involves the opportunity to explore and personalise awareness through experiential experience. The third lesson provides opportunities for integration with previous learning and creative expression.

The London Montessori Centre quotes that Montessori advised that the “three period lesson” of Seguin should be used. This addresses how to present a relevant vocabulary of language in conjunction with a piece of sensorial apparatus. For example in the first period the child hears the new language and vocabulary which is provided in association with the concrete example presented by the apparatus. In the second period the new vocabulary is presented to the child who then uses the apparatus to indicate the meaning. In the third period the child is asked questions about the apparatus so that he can illustrate that he has internalised the new vocabulary and can use it appropriately. (L.M.C.: 1982:43)

- Humour and Playfulness(Bernard,1965:94)

Identification of the Upper level of ZPD

When assessing the child’s upper level the adult may consider the following in relation to cognitive learning, creative activity, child development and teaching approaches.

- Independence – self-directed learning, self-discipline, establishment of new skills – physical, intellectual and social.

- Maturity ‘When action is internalised to form thought.’(Wood,1998: 22)‘The syntheses of : thought processes, daydreaming, and reasoning. (Meadows,2006:308)Confidence and competence. (Bernard,1965:76)

- Original and adaptive ideas – unusualness, a progression beyond the obvious, novel ideas, remote associations, ‘Intelligence enabled or promoted creativity.’ (Meadows,2006:253-257) ‘Divergent and adventuresome’ disposition. (Bernard,1965:75)

- Multisensory integration – intellectual association and the creation of new experiences that are unique and individual. Maximum transferability of learning to new situations.Transformation of evidence (Bruner,1973:225,402)- the ability to formulate/ verify/ revise. (Bernard,1965:90)

- ‘Beyond the information given.’ – intentional learning, hypothesis and prediction, inventive behaviour, a conception of natural forces, analysis of critical attributes, contingency planning, endurance and perseverance, integration of abstractness and concreteness within a learning experience, organic recall from memory, conceptual thinking .(Bruner,1973)

- Differentiation between thoughts and reality – perceptions and beliefs.

- Flexibility – fruitful application of previous learning into new situations, adaptability and the ability to accommodate random, chaotic or haphazard external conditions. (Bruner,1973:22&222)

- Socially meaningful activity – interpersonal communication, expansion of consciousness, the social ability to accommodate ‘cultural constraints and cultural amplifiers’. (Meadows,2006:311) Social Projection within the context of everyday situations related to the child’s own experience and feelings. Young children ‘come naturally to reason about their own and other people’s ambitions, fears, thoughts and feelings and to construct theories about how and why others act as they do………,’(Wood,1998:168)

- Identification of predictable patterns – ‘Intending to produce anticipated end results through his own actions’ the ability to ‘anticipate the impact…..’ (Wood,1998:21)

Occupational Versus Educational Activity

Our present extensive production of occupational toys sold in the high-street shops directs children’s play levels with pre-determined stimulus response activity and thereby encourages specified occupational play rather than child-directed learning. These occupational play activities are focussed on and/or dominated by the reception of sensory stimulus described above in (1). The child’s physical activity is either minimal or directly related to the repetition and/or prolonging of a specific sensory experience. Most manufactured toys present a specified range of appropriate play behaviour which is often specified by illustrative pictures and diagram. Imitative learning is emphasised and discovery learning and child-directed learning has minimal support.Man made environments can also be so highly stimulating that much of a child’s day can be occupied by sensory acclimatisation, i.e. getting familiar with the complexity of the intensely stimulating/changing environment. The child thereby gains a large amount of sensory input but little opportunity to actively explore in detail the context and interrelated nature of their different sensory experiences. Because children by nature need to be physically active they establish a repertoire of occupational responses, which provide opportunity to gain a sense of security within the context of prolonged strong sensory stimulation. For example the young child watching TV may suck a blanket or manipulate a cuddly toy, older children play on computer games that require fast repetitive button pushing movements. The author describes these predominantly receptive sensory occupations as entertainment. Entertainment here describes situations that hold a child’s focus in the first level of learning: sensory stimulus as above in (1)

Examples of entertainment are those activities that support an externally specified repertoire of active and/or passive responses to environmental stimulus:-

Television

Back ground TV, music or radio programmes

Repetitively reactive man-made toys and uniform building blocks which minimises the creative potential due to structural formality and pictures of predetermined designs.

Food stimulants (artificial colourings flavourings and preservatives, sugary sweets, chocolate, coffee and peppermint, alcohol.)

Over stimulating new and exciting environments that create abnormally high adrenalin levels for abnormally long periods.

Dominating adult speeds of activity and adult schedules.

Libertarianism, I can do anything I want, and you can do anything you want.

Rigid routines, a mechanical or theatrical style of response that excludes individuality and authenticity.

When the adult replaces a ‘I need to think about that ’ response with a ‘yes’, or the ‘I am sorry I can’t let you do that’ response with ‘it’s OK I’ll pretend it isn’t happening.’

When verbal communication overwhelms the child’s free expression and movements.

When physical punishment is so intense it dominates over the child’s self-directed play responses.

Adult initiated/motivated/enforced apprenticeship into clubs and classes, e.g. ballet or boxing. [Only when attendance is genuinely child motivated and appropriate to the child’s ability, personality, age and development, will the child develop the genuine engagement, empathy and interest related to meaningful learning.]

Adult entertainment: adult social events, cinema, theatre, dining out etc.

Child-directed Learning and Creativity

Learning is infinitely complex and the fluidity of creativity un-definable, this makes the definition of supportive adult practice very difficult. However, the bibliographies of Steiner and Montessori illustrate their teaching ability to influence child-directed learning and subsequent intellectual development. Steiner proposes that affective teaching practise is linked to the quality of creativity invoked within the teacher herself. This seems to require a Yin-Yang unity of abstract and concrete concepts of reality and consequences, together with an ability to teach within the child’s Zone of Proximal Development. This would appear to relate to the teacher’s capacity to incorporate creative thinking within her teaching practice; her ability to appropriately associate adventures within the child’s learning potential with an awareness of higher levels of sensitivity during ‘sensitive periods’.(Montessori and Vygotsky)

Abstract & Concrete Thinking

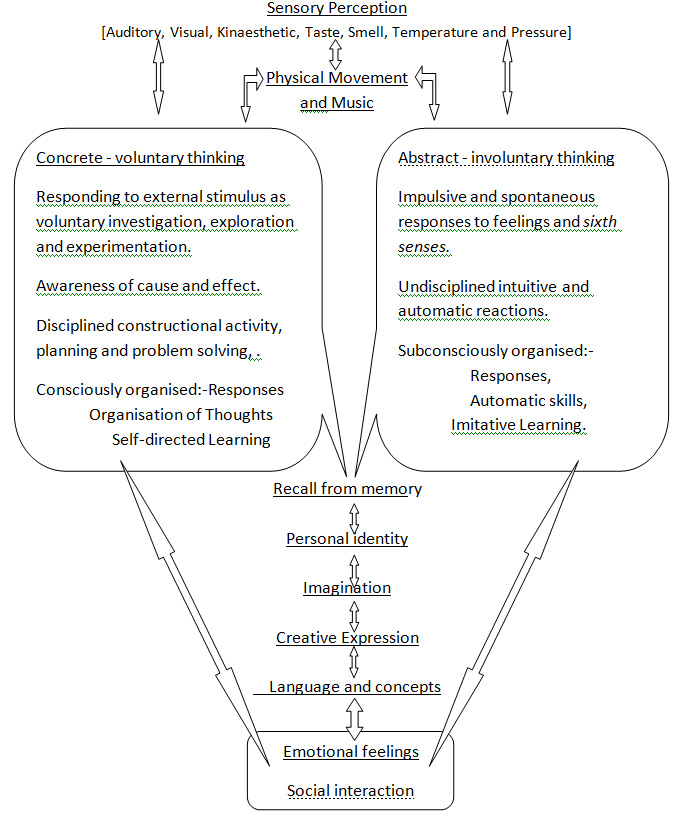

The followingdiagram has been designed by the author toillustratesher own understanding of associated areas of abstract and concrete development. It is important that everyone and especially children are encouraged to integrate functions in the brain in a balanced way that promotes more complex areas of learning and appropriate responses.

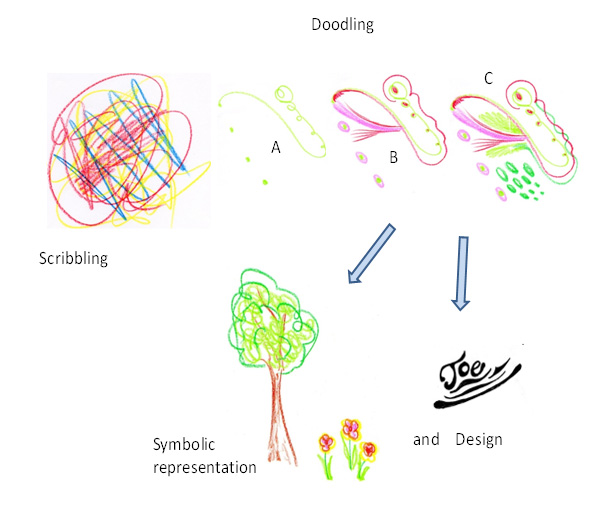

Child development from random movement to the integration of creative expression with creative production,

the integration of abstract inner feelings with concrete external activity.

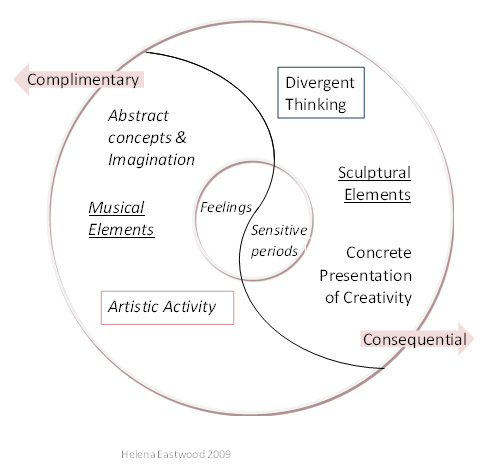

Child-directed learning inevitably involves an integration of concrete and abstract brain activity which Steiner described as the structural elements and musical elements. When these elements unite they create a sense of integration and harmony, e.g. imagination, poetry, eurythmy, problem solving.

This diagramme illustrates

Creativity as a union of environmental activity with feelings,

uniting fantasy with reality and facilitating the embodiment of joy described as enjoyment.

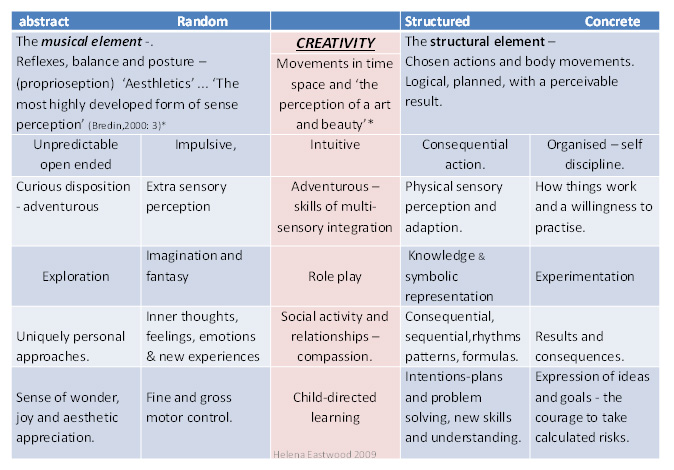

The contrasting lists below illustrate two types of thinkingwhich the author describes as abstract and concrete; Steiner describes as ‘the musical elements’ and ‘the sculptural elements’ (Steiner,1982:52)and Fisher describes as ‘a division between creative or exploratory thinking and critical or logically analytical reasoning’.

‘Creative———————————-critical

Exploratory——————————analytical

Inductive——————————-deductive

Hypothesis forming—————-hypothesis testing

Informal thinking——————-formal thinking

Adventurous thinking————–closed thinking(Bartlett)

Left-handed Thinking————-right-handed Thinking(Bruner)

Divergent thinking———–convergent thinking(Guildford)

Lateral thinking—————vertical thinking(De Bono)’ (Fisher, 1990:32)

However, high intellectual thinking abilities are not, it would seem, necessarily a pre-requisite for later notable levels of achievement.

‘…….:commonly high achievers are not predictable from early excellence so much as from their investment of time and energy.’ (Meadows 2006:257citing Radford1990)

The chart below unites the previous yin yang diagram and Fisher’s list of different types of thinking within a more practical perspective that may indeed be more representative of the child’s experiences of learning through play:-

Supporting Children’s Creativity and Creative thinking

Supporting Children’s Creativity and Creative thinking is acknowledged in the list of recommendations below:-

|

|

Integration of Concrete and Abstract Perspectives

Supporting enhanced creativity and self-directed learning.

The main focus for adult facilitation is meeting what the child is choosing to do rather than what result is desired and/or achieved. Never-the-less sometimes an adult’s experience and awareness of complimentary choices can provide good scaffolding for the child’s learning process. A good directive for adults wishing to support creative endeavours is

Simplify –For example:-

MAKE IT BIGGER

Outdoor activities -v- indoor activities e.g. at the stream -v- indoor water play; maypole dancing –v- sewing and table top weaving activities.

Make it slower…..-

| ‘With assistance, every child can do more than he can by himself – though only within the limits set by the state of his development.’ (Vygotsky,1986: 187) |

E.g. Badminton –v- tennis

Prioritise focus on a specific aspect of the skill.

e.g. Painting with prime colours on wet paper to make secondary colours.

Enrich the experience with diversity and/or a multisensory approach.

E.g. Supporting an area of interest with a suitable project and/or special outing.

Enhance motivation –within the context of useful skills, the child’s interests and abilities (scaffolding), personality and disposition.

Provide reflection and open ended questions

i.e.Questioning the question; identify successful activity with appropriate positive feedback and encouragement.

Encourage the child to lead/direct every aspect of the adult’s interaction and participation. Listen to every aspect of the child’s verbal and non-verbal communication.

Development is about moving beyond the limitations (mental, physical, emotional,) of the present moment into a future of greater potential. Adult assistance can thereby either compensate for developmental weaknesses by directing what to do or by actually doing the activity themselves. Alternatively the adult could scaffold the limits set by the child’s present level of development in such a way as to strengthen the weaknesses and encourage adventuring into new levels of doing; in this way further development is encouraged. This is the true art of teaching and the most effective form of caring and sharing